The BLF: Working Class Power in Action

The Revolutionary Legacy of the Builders Labourers Federation

This article is based on a talk given by the author at the Victorian Socialist Workers’ Caucus (VSWC) on Wednesday 26 March 2025. VSWC meets monthly at the Victorian Socialists Volunteer Centre.

The legacy of the Builders and Labourers Federation (BLF) is hidden in plain sight. Every day, Melbourne workers walk through a city shaped by the struggles of the BLF: preserved heritage buildings, protected parklands, community spaces. Yet few people know the history of the workers' movement responsible for this legacy. As socialists, we look to the highpoints of working-class struggle for inspiration and renewed hope, and we take the lessons of those struggles to be applied today.

While this article draws heavily on the history of New South Wales branch of the BLF, the Victorian branch was equally remarkable and was home to the first green bans, along with landmark victories that prevented demolition of iconic sites like the Queen Victoria Market, City Baths, and the Regent and Princess Theatres.

While it's no secret that strike days today are far from the level of the 60s or 70s, the working class remains an objective force in society and the spirit of working class resistance can always be reignited. As we delve into the history of the BLF, we'll see how a group of construction workers became one of the most radical and transformative activist forces in Australian labour history. Their story is not just a historical footnote, but a living blueprint for contemporary working-class resistance.

Building from below: the power of workers at the bottom

In mid-20th century Australia, builders' labourers performed the dirtiest, most dangerous work on construction sites - digging trenches, pouring concrete, and riding crane hooks hundreds of feet in the air. They were "at the very bottom of the pile" in the building industry. Their wages were terrible, deaths and injuries were commonplace, and basic amenities like toilets were often non-existent.

What makes their story so powerful isn't just what they achieved, but where they started. The BLF wasn’t always a militant union - it was initially weak, run by corrupt officials who were in the pocket of building bosses, covering workers hired by the hour, who were seen as unskilled and easily replaceable. These same downtrodden workers built one of the most powerful unions Australia has ever seen; but the transformation didn't happen overnight.

In Sydney, the battle for a democratic, fighting union took over a decade. Beginning in 1951, Jack Mundey, Joe Owens and other militants began the slow work of organising. They started by secretly leafleting workers on job sites, visiting them at home, and publishing a rank-and-file journal called Hoist. It was painfully slow work. Eighteen months in, they held their first public meeting - and just 15 workers showed up. Opposing the corrupt leadership often resulted in bashings and a demoralising election loss in 1958 led many to give up entirely, but the few who remained persistent finally won control in 1961.

Democracy in action: from workplace to social struggle

The new leadership radically democratised the union. With rank-and-file militants in control, the BLF:

Opened the union office during building hours so workers could actually access it

Limited officials to taking only a builder’s labourer's wage

Introduced six-year term limits for officials - then back to the tools

Put all major decisions to a vote by the members

Encouraged rank-and-file control on the job

Originally, most of the disputes the union took on involved basic workplace issues. They fought for fundamental rights like:

Having a first aid officer on site

Access to clean water

Suitable change rooms

Proper workers' compensation

Defending workers facing unfair dismissal

But these initial victories were transformative. In winning these basic rights, workers discovered something powerful: a profound sense of their collective strength. No problem seemed insurmountable. Radical workplace democracy wasn't just for show - it was the source of the union's power. This collective strength progressively translated into broader social struggles and, as their confidence grew, the union's scope expanded dramatically. Eventually, any issue involving workers would become the business of the BLF.

Taking control of production

The logic of increased workers’ control brings workers to not only question a company’s right to make a profit; they also begin to question their own role in a capitalist society. At some worksites this control was so immense that BLF members didn't just strike - they literally took over.

This was the case during construction of the Sydney Opera House in 1972, when workers staged a “work-in”. The Opera House construction site was a powder keg of tensions between bosses and workers and the seeds of conflict had been planted long before the dramatic event. The contractor responsible for building the rotating stages in the Opera and Drama theatres was notorious for its terrible management style. By 1972, they had already cycled through three managerial staff, with the union forcing out three foremen. It was not uncommon at this point in time for there to be 2-3 strikes per day.

The work-in began with a seemingly trivial incident: a fitter was sacked for jokingly throwing water over his mate during a strike. When the idea of a "work-in" was first proposed at a meeting, it was met with astonishment and laughter. However, after much debate, the workers surprisingly voted to support the radical tactic. Their plan was audacious: bring the sacked worker back onto the site without management approval.

For three days, they smuggled the worker on and off the job site, often keeping him in hiding but ensuring he participated in meal breaks and meetings. Remarkably, this first experiment was successful - the worker was not only reinstated but also paid for the days of his "work-in".

A subsequent dispute over wage inequality between fitters and riggers led to a black ban on fitter work, which brought construction to a halt. When the company retaliated by cancelling Saturday work, the workers, bouyed with the confidence of their first work-in, got down to business.

They began by literally expelling management from the site and seizing control of the project. They forcibly broke open toolboxes with crowbars, physically walked past supervisors who were trying to block them, and explicitly told management "go home or throw yourselves in the harbour." When management attempted to dismiss workers, they simply ignored them.

Remarkably, their self-management proved extraordinarily efficient, with workers reporting unprecedented enthusiasm and productivity. They eliminated work role demarcations, with tradesmen doing labourers' work and vice versa, and electing their own foremen and safety officers. If work ran out, they would dismantle and restart projects to maintain morale and discipline.

These workers proved that not only could workers run industry, they could do it better than when a boss was telling them what to do! The tactic ultimately proved successful - workers won forty-eight hours' pay for a thirty-five-hour week, the right to elect their own foremen, substantial redundancy payments, four weeks' annual leave with a 25 percent bonus, and other significant concessions.

The origins of green bans

The BLF didn't just transform workplace dynamics – they fundamentally reimagined the role of workers in society. Their “green ban” movement emerged from a profound understanding that labour is not just about wages, but about the broader impact of work on communities and the environment.

Drawing on the union movement's existing tradition of “black bans”- where the union imposed work stoppage or refused to work on a particular project, typically used to protest unfair labour practices - Jack Mundey coined the term 'green ban' in 1973 to describe a new form of industrial action. These were not simply work stoppages, but strategic interventions that challenged how society was built. The green bans focused on three critical areas:

Defending public open spaces

Protecting existing housing from destructive redevelopment

Preserving historically significant buildings that were not yet heritage-listed

The simple but radical politics of Green Bans

The underlying philosophy was radical in its simplicity. As Jack Mundey famously articulated:

“Yes, we want to build. However, we prefer to build urgently required hospitals, schools, other public utilities, high-quality flats, units and houses, provided they are designed with adequate concern for the environment, than to build ugly unimaginative architecturally bankrupt blocks of concrete and glass offices … Though we want all our members employed, we will not just become robots directed by developer-builders who value the dollar at the expense of the environment. More and more, we are going to determine which buildings we will build.”

This wasn't just environmental activism – it was a complete reimagining of the social responsibility of labour. By insisting that workers have a say in what they build and why, the BLF challenged the notion that development should be driven solely by profit.

Landmark Campaigns: Green Bans in Action

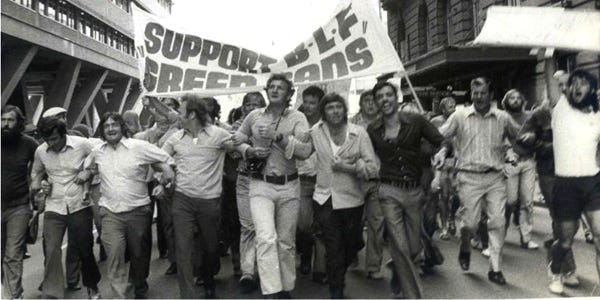

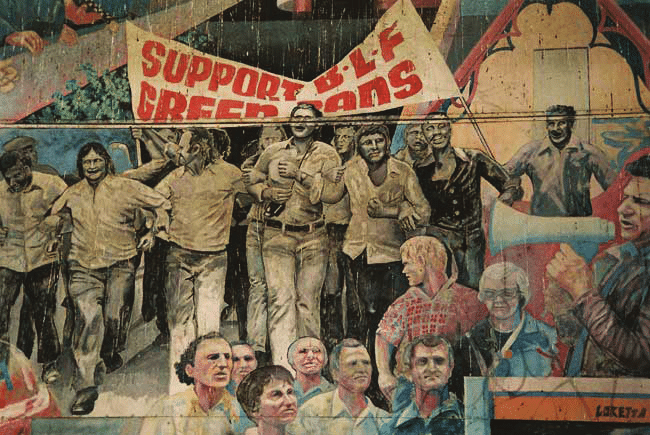

The movement's first significant victory came in Victoria when they prevented a developer from destroying a Carlton park. However, it was the campaign to save Kelly's Bush in Sydney that was arguably the most definitive moment for the green ban movement.

The Kelly's Bush dispute

When the smelter at Kelly’s bush closed in 1966, the land was sold to developer AV Jennings, who proposed constructing luxury houses on the site, not realising that this seemingly routine development plan would become the catalyst for an extraordinary community and union campaign.

The first spark of resistance came from local resident Betty James who, in July 1970, wrote a passionate letter to the Sydney Morning Herald, describing the land's natural beauty – its deep gullies filled with bracken fern, lilly pilly, and banksias. More than just describing a picturesque landscape, she highlighted the site's significant Aboriginal cultural heritage, including known sandstone carvings. By September 1970, a committee of local residents had formed – an all-female group led by Betty James. They called themselves the "Battlers for Kelly's Bush", although the local Hunter's Hill Council referred to them as the "thirteen bloody housewives".

In 1971, despite numerous protests, the minister for local government rezoned the land from 'reserved open space' to 'residential' – effectively clearing the way for development.

Union Solidarity in Action

Facing bureaucratic roadblocks, and knowing they needed more than local protest, the Battlers engaged the Builders Labourers Federation, understanding that the union's industrial muscle could transform their local struggle.

The BLF had a specific protocol: they would only impose a ban if there was genuine public support. So the Battlers organised a public meeting that drew over 600 people – a clear demonstration of community sentiment. On 17 June 1971, the BLF imposed their first green ban on the Kelly's Bush site.

The impact was immediate and profound. AV Jennings was forced to sell the land to the Hunter's Hill Council. It would take six more years of struggle, but in 1977, it was announced there would be no development at Kelly's Bush. By 1983, the land was permanently reserved for public use.

The campaign inspired similar efforts across Sydney and beyond. It led to protecting some of the oldest buildings in The Rocks, stopping a concrete sports stadium in Centennial Park, and blocking a carpark underneath the Botanic Gardens that would have threatened fig tree plantations.

What made Kelly's Bush so significant was not just its environmental preservation, but its radical reimagining of workers' power. The BLF showed that unions could do more than negotiate wages – they could be active agents of social and environmental justice, standing alongside communities to protect shared spaces and values.

Solidarity Beyond the Workplace: A Radical Vision of Collective Struggle

It was only natural then that the BLF's commitment to social justice extended beyond environmental protection and were channelled into issues of social justice too. The BLF was instrumental in:

Supporting Aboriginal land rights and the fight to save The Block in radical black Redfern

Opposing the Vietnam War

Fighting against South African apartheid

Conducting the world's first strike for gay rights

Supporting equal pay for women

A defining moment came in 1973 when BLF workers at Macquarie University walked off the job to protest the expulsion of a gay student, Jeremy Fisher in what is now called a pink ban. Union official Bob Pringle's response captured their principled approach: "It's the principle of the thing. They shouldn't pick on a bloke because of his sexuality."

Public housing defence

The Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) didn’t just go up against developers, they also went up against the state as an unprecedented defender of public housing. From 1971 to 1975, they implemented a strategic green ban in the inner Sydney Harbour-side suburb of The Rocks, directly confronting the NSW government's aggressive redevelopment plans.

The government had been systematically attempting to clear the neighbourhood by deliberately neglecting housing maintenance and dramatically raising rents—in some cases by up to 300 percent—to force out working-class residents. When the government proposed replacing the existing 416 residents with commercial developments, the BLF took a radical stand. They refused to work on any sites that would displace the community, effectively freezing the $500 million redevelopment scheme.

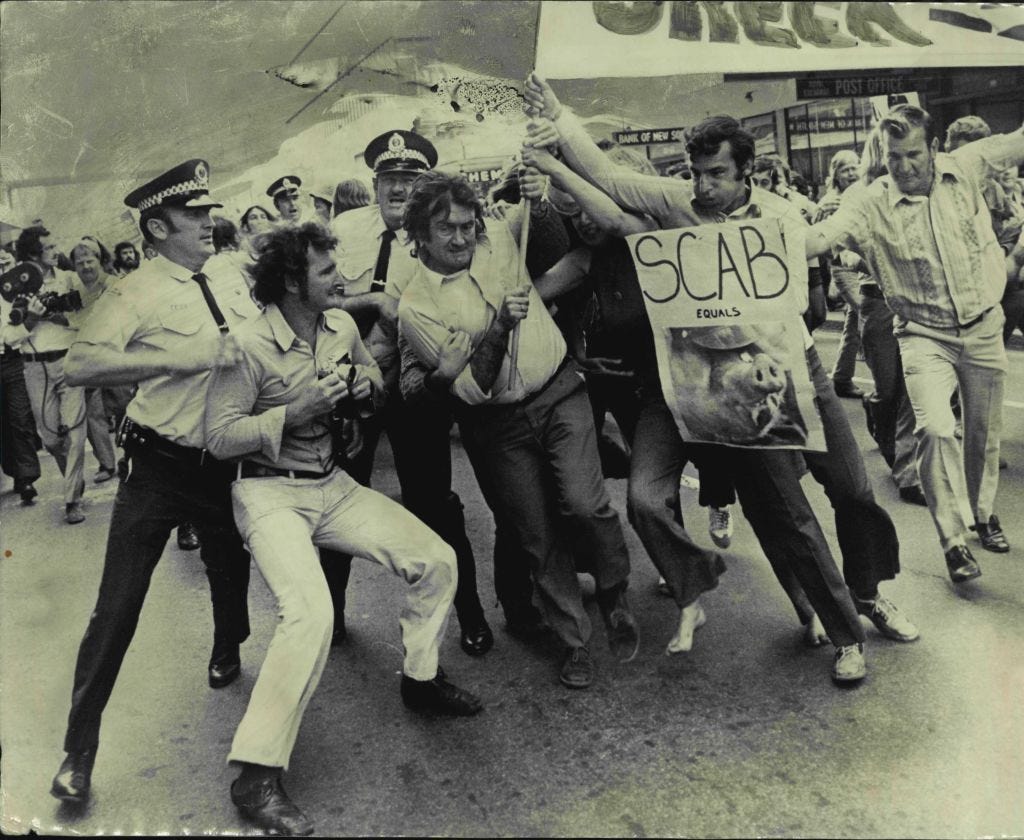

The culmination of their resistance occurred during a dramatic week in October 1973, when over 100 workers and community members conducted a day-long sit-in at the threatened Playfair Street site, facing police confrontation and mass arrests. Through sustained public pressure and their unwavering green ban, they transformed urban planning philosophy, preserving over 70 historic buildings and creating affordable community spaces.

The Politics Behind the Power

This extraordinary solidarity wasn't accidental. Heavily influenced by Communist Party organisers, the BLF understood that fighting oppression was essential to building working-class unity. They challenged the stereotype of blue-collar workers as socially conservative, proving that true solidarity transcends economic interests.

Their most radical act was transforming the very meaning of workers' power. They weren't just negotiating wages – they were questioning who benefits from labour and from development. By refusing to work on projects that would destroy community spaces or displace working-class residents, they demonstrated that workers could and should be active agents of social change.

We can't separate the BLF's militancy from its politics. The union's transformation was led by communists and socialists who spent years organising at the grassroots level. This politics of workers’ power from below informed everything they did, from their insistence on democratic control to their extension of solidarity to all oppressed groups; from their demand on having a say on what gets built and why, to their deeply held conviction that the working class can run society. Most importantly, the BLF understood what every socialist does: that workers’ greatest power lies at the point of production.

Lessons for Today's Struggles

What can we learn from the BLF as socialists organising today?

First, that even the most downtrodden workers can build tremendous power through persistent organising. The BLF didn't start with millions in the bank or paid staff - they started with a handful of militants leafletting on job sites.

Second, that democracy matters. Worker control wasn't just a slogan - it was practiced through limited tenure for officials, equal pay, and mass decision-making. By giving workers real power in their organisation, they built collective confidence and commitment. Members weren't passive recipients of union decisions but active participants in shaping their collective destiny.

Third, that class politics matters. The BLF understood that working class solidarity transcends narrow workplace issues. Their politics were fundamentally internationalist and intersectional, long before these terms became widely used. As Bobby Baker articulated, "if they were going to send workers off to war, then it was our business. If there were black guys working on building sites, then it was our business what was happening there."

Rebuilding Working-Class Power

In today's climate of industrial passivity and harsh anti-union laws, the BLF's example is more important than ever. Survey after survey shows workers want to join unions, want better wages and conditions, and, when given the opportunity, are prepared to fight and win.

Just as the BLF rose from being a marginal, overlooked workforce to a powerful social movement, we too can rebuild. As socialists we know this isn't about grand strategies or top-down directives. Instead its about combining the day-to-day fight over immediate conditions with the broader political vision that animated the BLF. It’s about building a rank-and-file that is democratic, militant, and controlled by workers themselves. This is because change doesn't cascade from the top - it erupts from the bottom, from the collective strength of people who decide they will no longer accept the status quo.

Further resources

Rocking the Foundations (1982 film, produced and directed by Pat Fiske)

The 1972 Sydney Opera House Work-In - Meredith Burgmann, Ray Jureidini, Verity Burgmann

When Sydney was touched by workers’ democracy - Jerome Small

‘I’m part of the union!’ How the Builders Labourers Federation set the benchmark - Liz Ross

The NSW BLF: The battle to tame the concrete jungle - Mick Armstrong

The Green Bans Movement: Workers' Power and Ecological Radicalism in Australia in the 1970s - Verity Burgmann

Making Change Happen. Black and White Activists talk to Kevin Cook about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics - Kevin Cook, Heather Goodall

Terrific work again Madi. Really enjoyed the original talk. Looking forward to the next socialist workers' caucus

The best talk! So great to see it published here!